Starting in 2026, I decided to live with two jobs.

My day job is the kind of work that has no retirement—slow, lifelong, always in progress.

My night job is built for an exit—intense, time-bound, designed to finish or transform into something else.

As I prepare to focus the next five years on bcdW, I’ve been forced to answer a question that people keep asking—more often than I expected:

“So, what do you do?”

I had planned to spend January shaping the language for that answer.

Instead, I’m in Medellín, Colombia, struggling with heavy exhaust and the smell of urine on the streets. Oddly, when a city becomes physically difficult, it makes me think about cities even more—what they are, what they should be, and why I can’t stop trying to redesign them.

I didn’t start dreaming of cities recently

Dreaming of cities is not new for me.

And yet—I’m not a sailor.

Still, I’ve been dreaming of ships for as long as I can remember.

Maybe my inner world has been floating on water for 36 years.

As a child, I was obsessed with a wind-driven ship. I didn’t know where it was going or who would be on board. But I couldn’t shake the feeling that a gigantic sleeping city existed somewhere near us—waiting.

I gave myself nicknames:

Windy Sea, and Captain.

That was 1992.

No one asked me to do it, but it felt as if the world had placed a steering wheel in my hands.

In my teens, I was a naïve socialist.

At the time, that wasn’t rare—many people privately carried similar thoughts. But as a high school student, saying it out loud wasn’t easy.

Looking back, it wasn’t politics that mattered most. It was a question:

What kind of world are we living in—and what kind of world could we build?

Even after being expelled from school three times (including high school), I never dropped that question.

Back then, I didn’t think in terms of modern nation-states. I wondered something simpler, almost ancient:

Could the idea of the city-state return—reborn in a new form?

Why do some cities make people lonely, while others connect them?

Why do certain systems produce exploitation, while others make people believe in community?

I didn’t organize these questions in academic language.

I raised them as a worldview.

My first organization was already a city metaphor

Around age 35, I built my first company and called it:

Cosmic Station & Associates

It’s the logo and cover image of Cosmic StatioN & Associates

The first sentence in the introduction was:

“We, aboard a spaceship, attempt to communicate with Earthlings.”

A phrase stayed with me from an old story:

When Columbus “discovered” a new land, some say the locals couldn’t “see” what they had no concept for.

So my mission became:

Make the invisible visible.

I didn’t realize it then, but the space station was my metaphor for a city.

The spaceship was a ship.

The “Earthlings” were generations, memory, and relationships.

That company didn’t last.

But the worldview never shut down.

Mystery Paul’s Ark: not an event, but a civic experiment

About ten years ago, I picked up the ship again—this time with clearer intent.

I started thinking about Noah’s Ark:

Technology as imagination after a flood

Ethics of choosing what survives

Urban design as a question of habitation

Archives as a way to preserve memory

I hosted a party called:

Mystery Paul’s Ark.

2015 Mystery Paul’s Ark party

the images of the party

It wasn’t just a social night.

It was a civic experiment—a performance about how we prepare a city for what comes after disaster.

In front of around sixty friends, I declared that I would move to New York.

At that time, I was especially focused on two words:

death and design.

Because a city, in the end, is the container for how people live—and how they leave.

The ship became a city, and the city became an industry

After moving to New York, a few years passed.

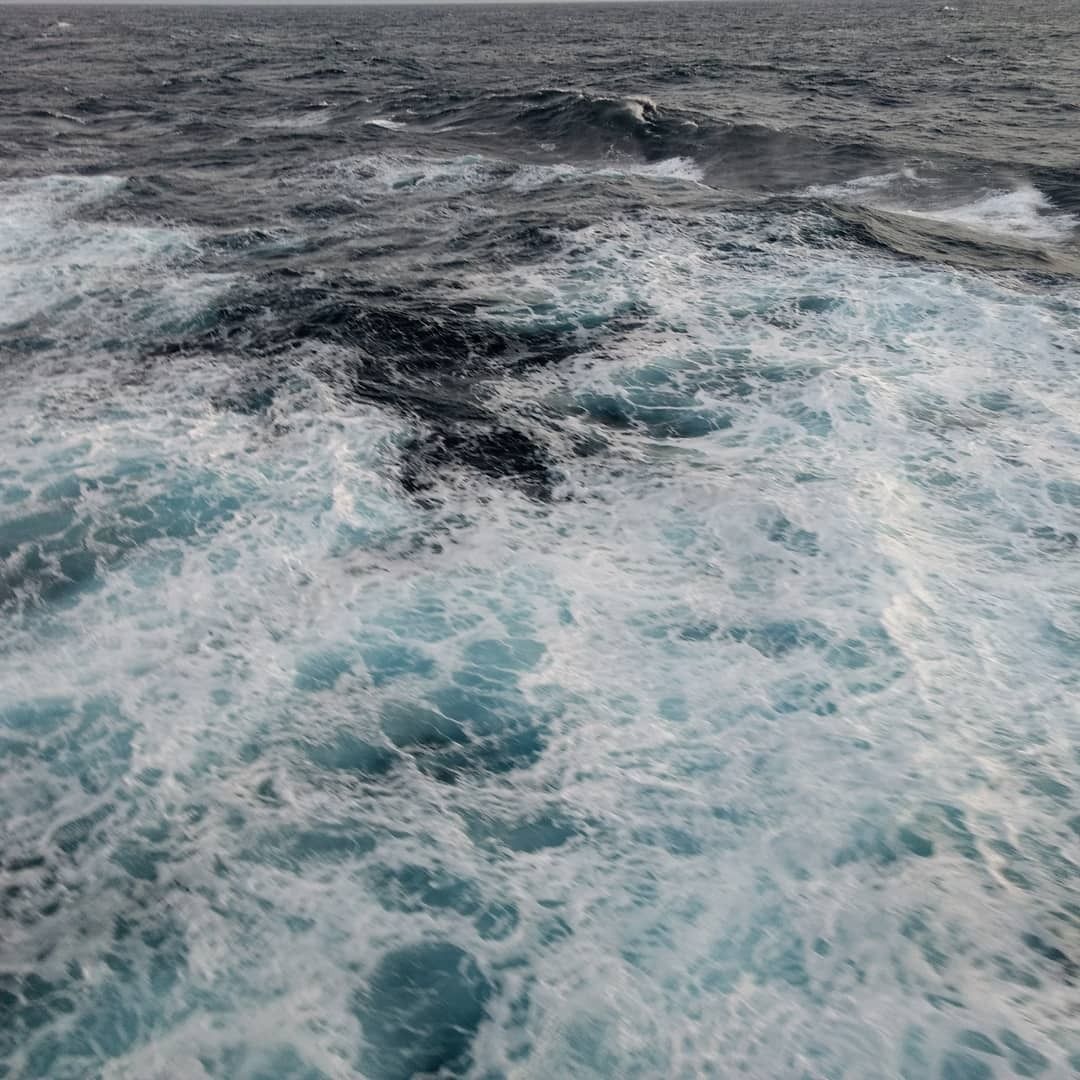

At one point, I crossed the Atlantic by cruise ship from London to New York.

In the middle of the ocean, I watched a single bird follow my cabin across the endless water—and I imagined Noah’s Ark again.

A wave in the Atlantic Ocean, captured from the Queen Mary 2.

But my question changed:

In an era of extreme productivity, what form would a modern ark take?

A past ark was about survival.

A future ark is about how to live.

That’s when a shape appeared in my mind:

A floating city.

A survival model for the age of climate change.

A living community connecting aging, generations, and everyday life.

A city designed to hold memory and archives.

That’s when I began to see cities as prototypes.

Not products, but systems—and systems require creators, operators, and constant upgrades.

Sim Eternal City: a future city as a prototype of civic nation.

My long-term flagship project became:

Sim Eternal City.

The ship became a city. further more, Civic Nation.

And the city, I began to believe, could become a new kind of selective, self-sustaining city-state—an intentional system of life.

Sim Eternal City asks:

How should a city function after climate crisis?

How do we archive generations and memory?

How will the past, Current and future generation evolve?

These questions are not only imagination.

They are systems—interwoven across policy, economy, technology, care, ecology, psychology, culture, and industry.

And here’s the real problem:

The person building this must call it a job.

But most people still don’t understand it as work.

When I say “I build cities,” they think architecture, real estate, or government.

What I mean is broader, slower, and more complex.

Still, I want to say it clearly:

Making a floating city visible has become my job.

And it isn’t a short-term ambition.

It’s the result of a 36-year trajectory.

People still ask: “So what do you do?”

I pause because the question isn’t really about industry.

It’s about identity.

If I translate my world into professional language, I might say:

Future City Creator

or

Urban Future & Memory Systems Creator

It’s long—but accurate.

Not someone who only pushes cities toward “the future,”

but someone who designs how cities carry memory, generations, care, and meaning—alongside infrastructure and technology.

So what is bcdW?

bcdW is my night job—and also the engine of my day job.

It is a five-year commitment to translate my worldview into structures people can understand, fund, and participate in.

If I want to live as a city creator, I have to turn the word “city” into daily actions: revenue, partnerships, projects, prototypes, and proofs.

That is what I’m building now.

I’m still on the same ship

Looking back, my life has constantly moved between ships and cities:

a teenage imagination of community

Windy Sea and Captain as a self-made identity

Cosmic Station & Associates and its spaceship narrative

Mystery Paul’s Ark and my move to New York

floating city thinking as urban design

Sim Eternal City as a worldview

These weren’t random moments.

They were a route—drawn long ago.

I’m still on the same ship.

But now, I’m ready to call it what it truly is:

a profession.

A life spent making the invisible visible—

redesigning the city as a system for survival, connection, and memory in an uncertain future.

Even in Medellín, even when the air is harsh, I can’t stop thinking:

Cities can hurt people.

And that’s exactly why they must be re-invented.

And I want that reinvention to be my work.

I design future cities and memory systems—and I’m building bcdW as the engine to make that work real in the world.